Cultural Appropriation Is Standard Christian Fare

Cultural appropriation—the art of appropriating aspects (songs, stories, apparel, traditions, rituals, etc.) of some (minority) culture by an entity that doesn’t inhabit that culture—seems to have secured its rank among the cardinal vices of our age. Those found guilty of said vice in fairly recent times include university choirs, various sports teams, and select individuals such as Jessica Krug and Rachel Dolezal (though Dolezal, it should be noted, succeeded to some extent in exonerating herself by pitting the secular virtue of “self-identification” against the secular vice of cultural appropriation).

I confess that most present-day vices and virtues fail to impress me, largely because they strike me as watered-down (if not parasitic) versions of vices/virtues with more substantial historical-moral roots and are almost invariably being touted in an obvious effort to secure the higher moral ground (read: “advantage”) in some largely inconsequential power play. That said, cultural appropriation has been on my mind of late, not so much because of any recent news story, but because of a conversation I had last week with a high school student who suffered through an 8th grade Bible class with me as her teacher several years ago. As we talked, my high school friend somewhat blithely accused a performing arts teacher at her current school (not my own) of “cultural appropriation” for requiring white students to perform roles in a play depicting black American slaves, presumably with the ultimate goal of expanding their acting abilities and inculcating in them the virtuous counterpart to cultural appropriation (namely, cultural appreciation).

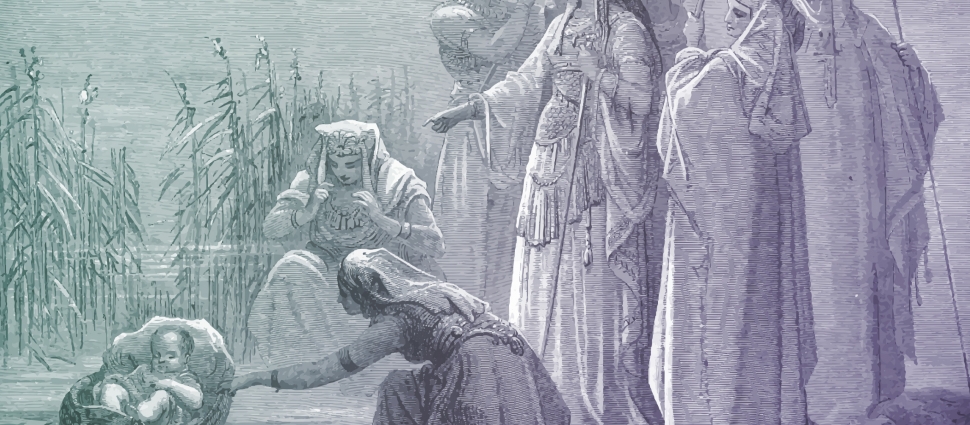

The verdict that I reached in my own moral musings this week is that cultural appropriation is really standard Christian fare. One might even call it critical to a proper understanding of the Christian gospel and experience of the Christian life. Relative to Christian living, it might be noted that Christians have dabbled (if not fully indulged) in the “vice” of cultural appropriation in, for example, their historic practice of praying, reciting, and singing Israel’s Psalms in order to give expression to their own experiences in life. A significant number of those Psalms relate Israel’s experiences of slavery in Egypt and/or captivity in Babylon. Christians for centuries have, without any obvious moral misgivings, prayed and recited those Psalms to give voice to their own anguish and faith in the midst of challenging national, familial, and personal circumstances.

Protestant traditions are specifically blameworthy in this regard insofar as they made it their custom to sing the Psalms as an aspect of corporate worship from an early date. Carl Trueman drew attention to this fact several years ago, pointing out that denominations like Scotland’s Free Church, who might on the surface seem particularly culpable of cultural appropriation for encouraging rousing renditions of, say, Psalm 105 or Psalm 137 in congregational worship, might be more culpable of “pastoral kindness” than anything else. The gradual demise of Psalm-singing in a large number of Protestant traditions over the years may have (unwittingly) served to align those traditions more closely to present-day moral positions on the “vice” of cultural appropriation. It has almost certainly, wittingly or not, rendered those same traditions less capable of meaningfully (i.e., emotively) articulating their struggles and triumphs in life. In summary, whatever one thinks about the emotive well-being of present-day Protestant denominations, the mere existence of the Psalter in the canon of Scripture would seem to suggest that God himself not only permits but intends us to appropriate another culture’s stories and songs (even, or perhaps especially, those that invoke a history of slavery and oppression) to give expression to our contemporary faith and feelings in the face of life’s varied difficulties.

If we turn our attention from Christian living to biblical exegesis and Christian faith, we discover that the Reformed tradition’s flirtation with cultural appropriation runs much deeper than the matter of Psalm-singing by itself indicates. The Reformed tradition has historically appropriated to the Christian church (and so to its own Reformed branch of the universal church) specific names, particular heroes, and, indeed, the entire history of Old Testament ethnic Israel. The Reformed tradition has, of course, merely followed Scripture’s lead in this regard. The apostle Peter calls New Testament believers “elect exiles of the Dispersion” (1 Pet. 1:1), thus appropriating to predominantly Gentile readers with cozy homes in ancient Roman cul-de-sacs (so to speak) Israel’s history of oppression at the hands of foreign powers. He goes several steps further by naming those same Gentile believers “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, [and] a holy nation” (1 Peter 2:9), all names unique to Old Testament Israel. Paul, similarly, appropriates ethnic Israel’s patriarch Abraham—and by implication, every hero in Israel’s history to whom God’s promises were repeated—to Gentile readers, telling them that “if [they] are Christ’s, then they are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to [God’s] promise” (Gal. 3:29).

The Reformed tradition, following such apostolic lead, has historically felt no qualms at all in blatantly naming the New Testament church the true Israel of God (see e.g. Gal. 6:16). Traditional dispensational readings of Scripture which distinguish Israel (and her promises) from the Church (and her promises) may have, again unwittingly, earned themselves some 21st century moral street cred by preserving, to some extent, Israel’s unique names, history, and promises. Covenant theologians in the Reformed tradition will, however, simply need to bite the bullet and acknowledge that their own reading of Scripture and the Christian practices they encourage on the basis of that reading (for instance, singing “Father Abraham” with their covenant children!) are a case of cultural appropriation on steroids.

One final instance, however, of cultural appropriation in the Christian tradition will (or should, at least) paint a target on every good Protestant. That instance is the historic Protestant practice of appropriating one very specific, heavily oppressed Jewish individual’s history to every genuine believer in Christ. Scripture teaches, of course, that every true believer is mystically united to Christ by the power of God’s Spirit. Each believer’s personal union with Christ serves as the basis for the imputation of that believer’s sin to Christ and the imputation of Christ’s righteousness to that believer (and so God’s verdict of righteous regarding the same). Each believer’s personal union with Christ equally serves as the basis for that believer’s gradual transformation into the image of Christ (who is, in turn, the proper image-bearer of his Father). Each believer’s personal union with Christ serves, then, as the basis for that believer’s prerogative, with the apostle Paul, to fully appropriate Jesus Christ’s personal history as if it were his or her own, even (or rather, especially) in that moment when Jesus Christ suffered beyond the experience of any other man or woman in human history, being executed, though entirely innocent, as a Roman criminal on a cross and assuming, in that same moment, the full wrath of God against sin. “I have been crucified with Christ,” Paul rather boldly claims in Galatians 2:20. By virtue of his own apostolic example, Paul encourages every believer to say the same; to appropriate, that is, the personal experience of a supposed criminal from an ethnic minority of the first century. Of course, the cultural appropriation (if you will) of Christ’s personal history has a positive flipside, since his personal history didn’t end with crucifixion. I can equally say with Paul that I have risen from the dead with Jesus Christ, have ascended with him, and have been seated with him at the Father’s right hand in heavenly places, so that in the coming ages God might pour the immeasurable riches of his kindness out upon me (Eph. 2:6-7). One day, of course, my subjective experience will catch up to the objective reality of my life established by God the Holy Spirit’s appropriation of Christ’s personal history to me. That, come to think of it, sounds like a promise and a future that render any moral opprobrium accrued in the present age eminently tolerable.

Cultural appropriation would seem, in the end, to be written into Christianity’s DNA. No need, so far as I’m concerned, for Christians to grovel or apologize for that, modern moral trends notwithstanding. No need either, to be clear, to be calloused or insensitive to the experiences of any peculiar people group. We can, rather, politely insist that our shared humanity permits us—indeed, requires us—to understand the experiences of people that differ from us (in gender, ethnicity, age, etc.). The universal category that encompasses us all (namely, image-bearers of God) ultimately trumps particular identities and gives us the right to claim some level of first-hand knowledge and experience of other peoples’ stories. We can, more to the point of my current rant, insist that genuine hope and identity in this world are, in fact, ultimately discovered in the appropriation of a particular, first-century Jewish man’s name and history as one’s own, and in the subsequent appropriation of that man’s national history and the promises made to that man’s ethnic forefathers. That specific instance of cultural appropriation is no crime. It is, rather, our only hope for forgiveness, true identity, meaningful inheritance, and good music to sing.

Aaron Denlinger (PhD, University of Aberdeen) is the Department Head of Latin and Bible at Arma Dei Academy in Highlands Ranch, CO. He has written on church history and historical theology in various journals, collections, and other publications, including Reformation Theology (Crossway, 2017).

Related Links

Podcast: "Race and Covenant"

"Cultural Appropriation that is Pastoral Kindness" by Carl Trueman

"Longing for a Multi-Ethnic Church" by Caleb Cangelosi

"Exodus and Liberation," review by Timothy Gombis

Christ and Culture, with Russell Moore, Carl Trueman, and Eric Redmond

Our Creed: For Every Culture and Every Generation by Mark Johnston