Will the Real Potiphar's Wife Please Stand?

May 8, 2018

“We should be friends,” quoth Potiphar’s wife;

but Joseph turned, and ran for his life.

“Avoidance is not purity!,”

she cried; but he ignored her plea.

One example from Scripture that I often hear to support the Mike Pence or Billy Graham Rule is Potiphar’s wife. I’ve heard, “If Joseph followed the Mike Pence Rule, he would never have gotten himself in this trouble.” He is also used as a warning for men not to trust women's accusations of sexual abuse. But I have to say, I was quite surprised when someone directed me  to Eric Hutchinson’s jab at my upcoming book, on Mere Orthodoxy of all places, in the form of an “Ode on the Pence Rule.” It opens with the above quote.

to Eric Hutchinson’s jab at my upcoming book, on Mere Orthodoxy of all places, in the form of an “Ode on the Pence Rule.” It opens with the above quote.

to Eric Hutchinson’s jab at my upcoming book, on Mere Orthodoxy of all places, in the form of an “Ode on the Pence Rule.” It opens with the above quote.

to Eric Hutchinson’s jab at my upcoming book, on Mere Orthodoxy of all places, in the form of an “Ode on the Pence Rule.” It opens with the above quote.This first stanza compares me to Potiphar’s wife, using the title and subtitle of my upcoming book as her words. That is quite a caricaturization! I am to be equated with a seductress sexual predator. And so is the idea of friendship. Hutchinson introduces the piece with a quote: “Can a man take fire in his bosom, and his clothes not be burned?”–King Solomon. I’m unsure: am I the fire in the bosom, or is friendship?

I know that Hutchinson is taking some poetic license here with the point he is trying to make, but I am flummoxed at the portrayal of this biblical account and the straw man that he sets up in which to warn others about my book. First, let me affirm that there are both male and female sexual predators out there, and that we are all to use discernment and wisdom in our relationships. Pushing back against the Pence Rule does not mean that we throw caution and common sense out the window.

The first half of my book addresses all the reasons that men and women cannot be friends: we’re letting the wrong voices tell us who we are (no, I’m not Potipher’s wife!), we don’t view each other holistically, we don’t know our mission, we misunderstand the nature of purity, we’re immature and fearful, we’ve forgotten what friendship really is, and we’ve overlooked our biblical status as brothers and sisters. These are all reasons that would hinder any possibility of friendship. For example, if a man could only see me as a sexual temptress who may harm his reputation, then he obviously isn’t a friend and it would be unwise of me to pretend so. You can’t be friends with everyone.

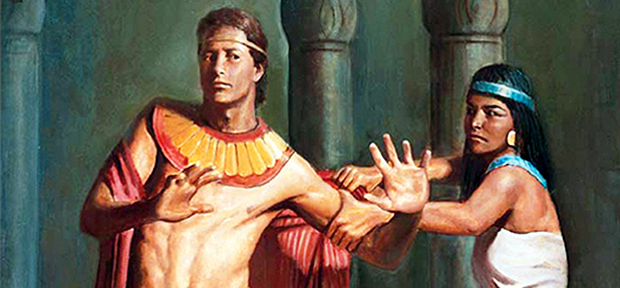

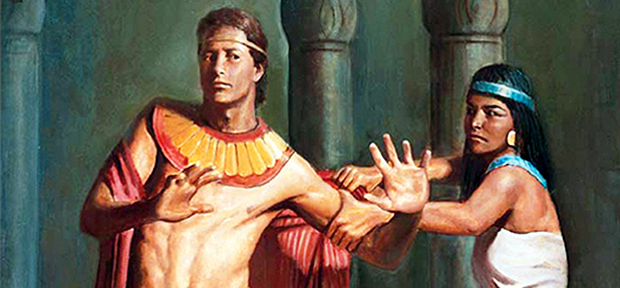

Hutchinson is right that you can’t be friends with Potipher’s wife. But we all know that is not what she was suggesting. This account found in Genesis 39 is not about friendship or men and women setting up boundaries. It’s about God’s sovereignty and his faithfulness to his promises to Joseph as we see this pattern of humiliation and exaltation in his life. We see that God is with Joseph, even as he is sold into slavery. We see the divine providence of an aristocrat acquiring him, finding favor in him, and setting him over his household. Interestingly, Scripture adds the line, “Now Joseph was well-built and handsome” (Gen. 39:6). We barely ever see a male described this way in Scripture. Women may lean in a little here because we know the tension of being described this way in the work place. It makes you a target in these kinds of stories. We know where it’s going.

And so as Moses sets up the reader, the very next line describes Potiphar’s wife’s lustful desire to have sex with Joseph. Bruce Walke quotes an insightful line from Sarna, “’She, the mistress of the house, is a slave to her lust for her husband’s slave!’” (520). The reader is not thinking about the possibility of friendship here. It’s pure lust, plain and simple.

And, Joseph could not just avoid her. He had to do his job. He is her husband’s slave! I’m sure he avoided her as much as he could. But he was in a situation where he had to endure the harassment. He even tries reasoning with her, that he would never “do this immense evil” of a sex act with her to his boss or as a sin against God. Joseph is virtuous even as she continues to harass him. And when she finally gets him alone, as predators have a way of conniving, he shows integrity. This is like #MeToo in reverse. Yes, men and women can both be sexual harassers and predators. But as we see in this account, usually the consequences are different. A similar situation ends differently for Bathsheba.

Joseph seems to have a bit of bad juju when it comes to coats. Potiphar’s wife aggressively grabs his outer garment, trying to force herself on him. But Joseph is stronger and he flees this attack, leaving his garment behind. This is when she cunningly works out the scheme to turn the tables on Joseph as the attacker. Men like to point to Potiphar’s wife as the object lesson for the Pence Rule to teach potential leaders about women who make false charges. Yes, that does happen. And it is ungodly and very bad. But that isn’t the thrust of the text: avoid women because you never know when they are going to pull false charges on you.

Waltke rightly points to the theme that God is with Joseph, and that “Joseph must trust God even in the face of unjust treatment. He is learning to put aside cloaks, trusting the Lord to clothe him with dignity and honor” (522). And unlike the many exploitations that we read about in #MeToo stories, “his refusal of Potiphar’s wife’s advances entails that he does not take advantage of his superior physique to dispossess his master but rather accepts his God-given social standing as a slave. Joseph participates in the eternal covenant: he has the law of God in his heart” (523). Waltke reminds the reader that this humiliation/exaltation in the life of Joseph typologically points to the life of the Israelites, and ultimately to Jesus.

Hutchinson compares both me and friendship with women to Potiphar’s wife, which leads men to the promiscuity of King Solomon. His Ode on the Pence Rule contrasts my so-called voice with that of reason,

Joseph, he’s so dull and boring;

Solomon is clearly soaring.

Joseph, self-protecting–tired;

Solomon, enlightened–wired.

I do write against the prevalent evangelical morality of individualistic self-protection that places a purely negative responsibility in our relationship before God and with others. Joseph is anything but boring and self-protecting in this account. He exercised character and virtue, taking the hits to his reputation while trusting in the Lord. We see faithfulness and holiness promoted in this story, not mere self-protection.

Fortunately we are not left with the false dichotomy at the end of Hutchinson’s Ode:

And so, dear readers, you can see

the choice in front of you and me.

To be like Joseph? That’s a shame.

But Solomon? Well, he’s got game–

his dad was rich, sent him to Yale,

while rustic Joseph went to jail.