Chapter 29.5, 6

August 1, 2013

v. The outward elements in this sacrament, duly set apart to the uses ordained by Christ, have such relation to Him crucified, as that, truly, yet sacramentally only, they are sometimes called by the name of the things they represent, to wit, the body and blood of Christ; albeit, in substance and nature, they still remain truly and only bread and wine, as they were before.

vi. That doctrine which maintains a change of the substance of bread and wine, into the substance of Christ's body and blood (commonly called transubstantiation) by consecration of a priest, or by any other way, is repugnant, not to Scripture alone, but even to common sense, and reason; overthroweth the nature of the sacrament, and hath been, and is, the cause of manifold superstitions; yea, of gross idolatries.

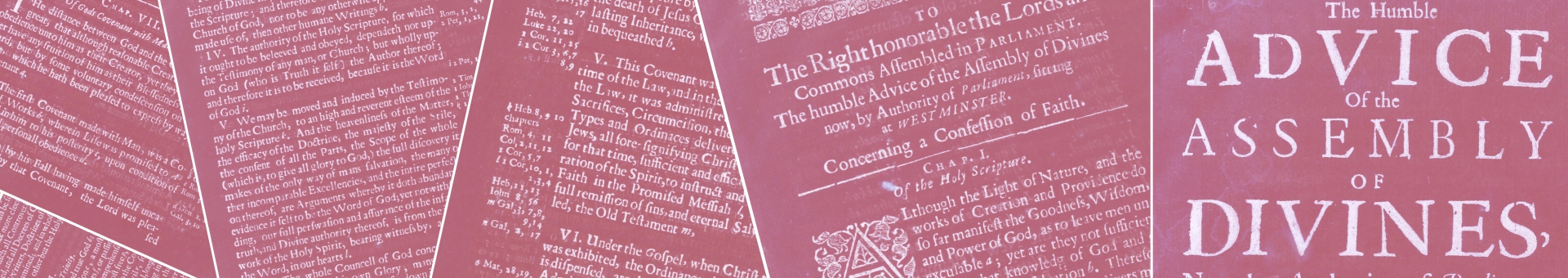

A Reader's Guide to the Sacraments

The fifth paragraph of the chapter offers a condensed reader's guide to the sacramental sections of the Bible, one of a number of such guides to Bible readers found in the Confession. It is designed to explain the vivid language used in Scripture to describe the Lord's supper: 'The outward elements in this sacrament', the bread and the wine, when 'duly set apart to the uses ordained by Christ', have such a close 'relation to Him crucified' that 'they are sometimes called by the name of the things they represent'.

We see this kind of language, for example, in Matthew 26:26-28. There 'Jesus took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to the disciples, and said, "Take, eat; this is my body." And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, saying, "Drink of it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant"'. The Westminster assembly's observation here is that Jesus did not say that the bread was like his body. He did not say that the wine was like his blood. He effectively, and shockingly, told his disciples to eat his body and drink his blood. The Westminster assembly's conclusion here is that what Jesus spoke, he spoke 'truly'. That is to say, there is nothing inappropriate or problematic about this kind of talk. It is just as acceptable for us to use this language today as it was for Jesus to use that language himself. He substituted the reality for the symbol, instead of the symbol for the reality. And so can we.

Evidently Jesus spoke this way because his sacrament and his sacrifice are so closely related; because the symbol chosen by Christ is so perfectly suited to represent himself. Nonetheless Christ's statement (made by a Saviour of flesh and blood) was true in a sacramental sense only. That is to say, the bread is a true symbol of Christ's flesh. In substance, in nature, the bread is bread and the wine is wine.

The interchange between symbol and substance is amply illustrated in 1 Corinthians 11, where Paul moves back and forth between mentioning 'the body and blood of the Lord' (once, referring to the crucifixion and the supper), and eating the bread and drinking the cup (three times, referring to the supper). The Apostle's continued references to the bread and cup illustrate the fact that references to 'the body and blood of the Lord' do not change the fact that even after these common elements are properly set apart for holy use 'they still remain truly and only bread and wine, as they were before'.

The Physical Presence of Christ in the Supper: The Trouble with Transubstantiation

If the fifth paragraph's instructions on reading biblical language is correct, then the truth of the sixth paragraph carries real force. The Roman Catholic 'doctrine which maintains a change of the substance of bread and wine, into the substance of Christ's body and blood (commonly called transubstantiation)' is simply incorrect. The doctrine of transubstantiation teaches that when the elements of bread and wine are consecrated, or ceremonially set apart by a priest, that the real substance of the bread and wine changes into flesh and blood even though all the apparent characteristics of the bread and wine don't change. The bread still looks and feels and smells and tastes (and if you drop enough of it on the floor it still sounds) like bread. The wine still tingles on the tongue and smells like the South of France or Napa Valley. But Roman Catholics are taught that it is really Christ's flesh and blood.

Transubstantiation was the dominant theory, but by no means the only theory, employed to explain how the elements of the supper could become the body and blood of the Lord. Here the Westminster assembly is rejecting not just transubstantiation, but any theory that attempted to justify a doctrine of the real physical presence of Christ. Neither the 'consecration of a priest', nor any other special words or actions, are capable of changing the substance of the elements of the Lord's supper. The idea of transubstantiation or any similar theory really is 'repugnant, not to Scripture alone, but even to common sense, and reason'. Without doubt it is contrary to Scripture. After all, as the resurrected Jesus explained to his disciples, he has normal 'flesh and blood' (Lk. 24:39). As Peter preached at Pentecost, heaven has received Jesus and will keep him until all things are restored at the last day (Acts 3:21). We celebrate the supper 'in remembrance' of Jesus, but 'remembering' is certainly an odd thing to do if Jesus is actually present with us bodily, first on the table, and then in our mouths (1 Cor. 11:24-26). Angels once had to tell people standing around an empty tomb, 'He is not here, but has risen' (Luke 24:6). We sometimes need to tell people standing around the Lord's table, 'He is not here, but has ascended'.

Transubstantiation and the family of associated theories are also contrary to common sense. We should not require a simile in order to identify a metaphor. When Jesus stated that the bread or wine was his body or blood, we should not need for him to spell out that he means that the bread or wine 'is like' his body or blood. It is no exaggeration to say that the idea of a physical presence of our Lord in the Lord's supper theologically and linguistically 'overthrows the nature of the sacrament' but also, historically, has been the cause of many superstitions - yes even obscene idolatries.

Dr. Chad B. Van Dixhoorn is Professor of Church History at Reformed Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. and associate pastor of Grace Orthodox Presbyterian Church in Vienna, Virginia. This article is taken from his forthcoming commentary on the Confession, published by the Banner of Truth Trust.