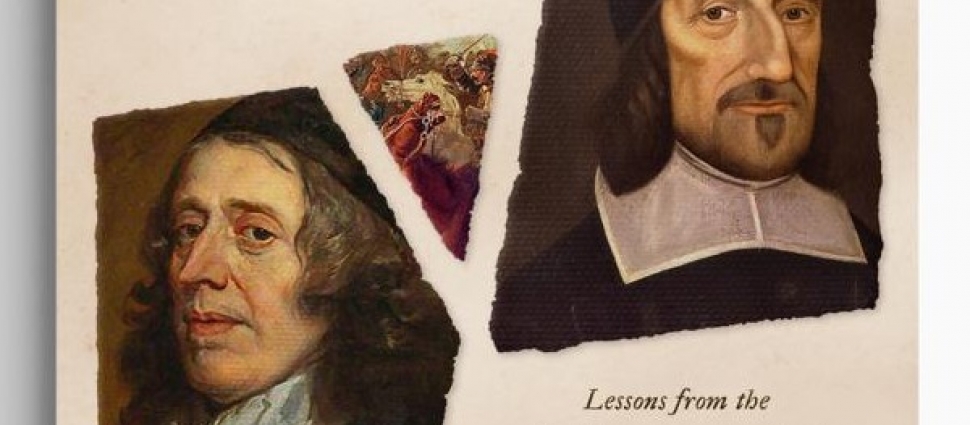

When Great Men Collide (Review of When Christians Disagree)

Following the tumultuous years of the mid-Seventeenth Century, two titans of English Puritanism left an especially enduring imprint upon church history. For centuries, many Protestant ministers have dedicated feet—yes, feet—of shelf-space to the published works of both John Owen (1616-83) and Richard Baxter (1615-91). However, Owen and Baxter were anything but friendly to one another.

In “When Christians Disagree: Lessons from the Fractured Relationship of John Owen and Richard Baxter” (Crossway, 2024), historian Tim Cooper of the University of Otago in New Zealand explores the theological, historical, and biographical dimensions of Owen’s and Baxter’s deeply personal difficulties. Along the way, he highlights salient lessons for those wishing to promote unity in the church today. What Cooper has produced is an eminently practical popular-level treatment of church history. In sharing it with ministry associates and fellow elders (in my church and beyond), I have referred to it as a “homiletical history.” I am thankful to my friend Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) Ruling Elder (and former General Assembly Moderator) Howie Donahoe for gifting me a copy of this title at the end of last year.

Theological Differences

The relatively well-known theological disagreements between Owen and Baxter center around their variant views on soteriology, or doctrine of salvation. Simply (and charitably) put, Owen emphasized the objective and eternal aspect of God’s sovereign grace in salvation, and Baxter pressed the subjective aspects of personal holiness and individual responsibility. In his zeal to confront the dangerous theological error of Antinomianism—which teaches that Christians should not be concerned with keeping God’s Law as a rule for life—Baxter articulated a view of justification that smacks of Neonomianism—a distortion of the gospel that teaches that good works are necessary to be reckoned righteous (i.e. properly justified) in the final judgment of God.

Though Owen and Baxter shared much common ground, they came into theological conflict in print when Baxter critiqued Owen on a fine point of doctrine concerning Christ’s substitutionary atonement in 1649. Thus began a longstanding, if somewhat accidental, animosity between the two theologians. As important as their theological differences were, however, Cooper suggests that their disagreements rested on a bedrock of important historical and personal factors.

Historical Differences

From our vantage point nearly 400 years later, Owen and Baxter look very similar. Both were Nonconformists, resistant to top-down enforcement of manmade practices in worship as advocated by the Arminian Archbishop William Laud (1573-1645) of the Church of England. Both were Puritans, desiring a thoroughgoing reformation of doctrine and religious worship in the Church. Both were Calvinists committed to God’s sovereignty in salvation. Both lived through the horrors of the English Civil War, in which an estimated 200,000 Britons—or 4.5% of the population—lost their lives.

However, their life experiences were dramatically different. Owen was highly educated and politically well-connected. Though precocious, Baxter was self-educated and lived at the margins of English politics and society. Owen spent the war years in relative safety and peace, encountering very little of the horrors of war as he ministered to high-ranking military officers, politicians, and scholars. Baxter accompanied soldiers in their sieges and skirmishes as a battlefield chaplain, witnessing firsthand some of the bloodiest scenes afforded by the War.

Lessons to Learn for Today

At the end of each chapter, Cooper includes questions for personal reflection and group discussion. With the help of these prompts, readers can meditate upon some of the most important lessons to be gleaned from the strained (and painfully awkward) interactions between Owen and Baxter. For example, as Cooper asks, “How much does unity matter? Should we try to set aside genuine and legitimate disagreement to preserve unity? If so, how should we go about it? Are we to preserve unity at all costs? In what circumstances, if any, is disunity a necessary (if regrettable) outcome of holding to the truth as we see it?” (101). In our age of rapid (and oftentimes rash) communication, these are important questions for all those who wish “to preserve the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph. 3:4).

Though Cooper emphasizes the circumstantial and personal aspects of these men and their “collision” (as he puts it), there is another important lesson to draw out of this account. Theology matters. By no means does Cooper ignore the theological dimension of the dispute. He dedicates an entire chapter to “Theology.” As he admits, “The trouble is that while they shared an enormous amount of common ground, they stood back-to-back, looking in opposite directions and subject to opposite fears… These underlying fears made it extremely difficult for each man to see in the other the many points they held in common. Rather, each one saw the other as aiding and abetting the enemy” (69). All these years later, some readers might risk hastily dismissing the theological divide between these men as either frivolous or inconsequential in the light of more weighty historical realities.

The differences between Owen and Baxter may be minor and obscure in the eyes of the world, but their theological disagreements (certainly compounded with personal factors) had direct and significant bearing on their mutual dislike. This is nothing short of tragic, for our theology should do precisely the opposite. True theology—and the discussions that help us align our theology more closely with God’s Word—ought to guide us into peace and reconciliation between brothers. The single most important theological truth to lead us through the fog of personal conflict and disagreement is our doctrine of God. Insofar as Christians believe that “God is love” (1 Jn. 4:8, 16), then they will seek to “walk in love” (Eph. 5:2) with one another, trusting that He is in control of history to order it to the church’s ultimate good (Rom. 8:28).

Zachary Groff (MDiv, Greenville Presbyterian Theological Seminary) is Pastor of Antioch Presbyterian Church (PCA) in Woodruff, SC, and he serves as Managing Editor of The Confessional Journal and as Editor-in-Chief of the Presbyterian Polity website.