What About B.O.B.s?

Note: Minor plot spoilers ahead.

I picked up War and Peace for the first time ten years ago on a family vacation, read 200 of its 1300 pages, and then set it down for the decade. I didn’t have time to follow the meandering paths of five noble Russian families through the Napoleonic Wars. I didn’t have the attention span for a 200-page plot setup. I couldn’t remember the myriad of characters, or endure the narrator’s historical analysis, or grasp the expansive history. But most of all, I didn’t have time for fiction when there is so much to read of Doctrine, Theology, and spiritual life. How could I read “for pleasure” when I was already pressed with studying, writing, and shepherding?

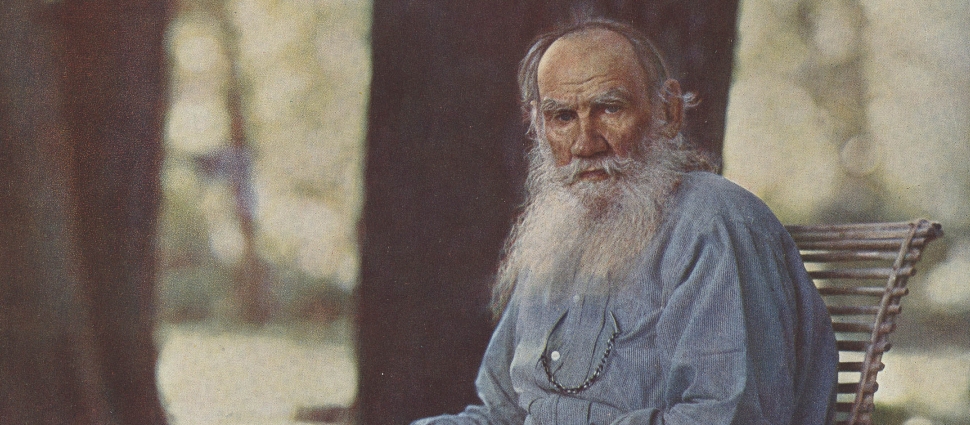

This summer, in the midst of an international transition and the global pandemic, I picked up Tolstoy’s treasure again and read it from cover to cover. What I found in these half million words was more than I expected: I found an antidote to our instant world, an answer to the vitriolic tweet-cycle, and an ally in my spiritual life.

I am now convinced that reading Big Old Books (B.O.B.s) is a useful habit for all Christians, especially those who desire to understand our current culture and engage it with the good news of Christ.

1. B.O.B.s as an antidote to an instant world.

“. . . when the fullness of time had come . . .” Gal 4:4

The majority of modern culture, from commercials to food labels, is aimed to trigger a chemical reaction in your body that will elicit a response. Buy this car. Eat this guacamole. Watch this series. A book that waits until page three for the inciting incident is left to collect dust on the shelf. A movie without an explosion (or car chase, or alien invasion, etc) in the opening scene is relegated to the box office also-rans. We in the West are not good at waiting for anything. We want our reaction and we want it now.

And so, when we take up a B.O.B. which doesn’t move out of first gear until page 250, we protest this modern malady. I noticed, as I made my way through War and Peace, a lowered heart rate, a more focused mind, and a decluttered consciousness. Like attending a symphony directly after a rock concert, my body adjusted to a different rhythm and new melodies. The pacing of older books can recalibrate our own pacing.

Take Pierre, for example, the “generously proportioned young man with close-cropped hair and spectacles” who is introduced on page 11. He is the illegitimate son of the wealthy Count Bezukhov who is on his deathbed in Moscow. Pierre is a passionate idealist whose passivity and penchant for lechery results in a listless life of unrealized principles. Eighty pages later, when he is revealed as the Count’s lone heir, Pierre is transformed into one of the wealthiest men in Russia. However, his fortunate turn of fate leads him deeper into his bad character. His passivity results in an unhappy marriage. His social station increases his hedonistic unhappiness. His wealth prevents him from finding purpose in life.

Pierre stumbles on through a thousand pages, a three-dimensional character in a three-dimensional world, searching for goodness, truth, and beauty. He dabbles in strict religiosity. He seeks meaning in humanitarianism. He attempts noble deeds. But the purpose he longs for remains elusive. Nothing is instantaneous for Pierre, just like our world. Spending time with characters like Pierre, especially in lieu of “three-steps to transforming your . . .” books, remind us that life is complicated, change is complicated, and reality is three-dimensional.

2. B.O.B.s as an answer to the tweet-cycle.

“ . . . that no one may deceive you by fine-sounding arguments.” Col 2:4

One of the great challenges we face in our world, and in the church, is the inability to have an extended and nuanced conversation. Ideas are reduced to sound bites and judged as such. This is true in the political and theological spheres. However, the gospel is too robust for a tweet. Our theology is too complex for a 60 second news clip. When Paul discovered heterodoxy in a church, he did not tweet at them, or even send them an email. He wrote them a sweeping theological treatise like Galatians or Romans. Even the shorter letters of John and Peter contain a nuance rarely found today.

One of the reasons Tolstoy wrote War and Peace, was to correct the (in his opinion) errant, surface level judgments of Napoleon’s foray into Russia. Throughout the novel he takes a break from the narrative to confront historians and their “simple-minded certitude” (667) regarding the events of 1812. Is history driven by the wisdom or failure of great men? Do armies win because of planning and strategy, or bravery and fortitude? Tolstoy rejects most of these approaches for the “ocean of history” (1259) which sweeps men and nations to and fro. In other words, history is not as simple as the story of great leaders or great strategists, but the sum of millions of individual choices and uncontrollable forces cascading into reality. Truly great leaders, like the Russian General Kutuzov, don’t try to shape history, but understand that “patience and time, these are my heroes of the battlefield.” (1139)

Whether we agree with Tolstoy’s analysis of history in general, or the French invasion of Russia in specific (which most of his contemporary historians did not), we can recognize his attempt at a de-politicized and de-nationalized review of an important historical event. He pursued a nuanced view of a polarized event.

You don’t beat a tweet with a harsher tweet. You don’t silence a sound bite with a louder sound bite. You drown them in the deep sea of slowly developed ideas. You bury them in the pages of nuanced and mature perspective. This is something we can all grow in.

3. B.O.B.s as an ally in our spiritual life.

“Let us test and examine our ways . . .” Lam 3:40

Not all Big Old Books are spiritually beneficial, but most classics have survived because they plunge the pen deeply into the reality of human life. As we spend hours observing the life of another—be it Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, or Churchill in the The Last Lion, or Pierre in War and Peace—we cannot help but reflect on our own life and the state of our souls.

The theme that challenged me in in War and Peace is the role of suffering in transformation. All of the main characters sought happiness and purpose by means of connections, wealth, and privilege. None of them found it except through difficulty, brokenness, and loss.

Poor, plain Princess Marya Bolkonsky spends the majority of the book trapped in her country estate with her verbally abusive father. She refuses an escape through marriage in order to care for her father. To survive the hostile environment, she pursues a deeper inner life through spiritual practices. It is not until the end of the book that we see the fruit of her efforts: “For the first time in her life all the pure, inner spirituality that she had worked so hard to achieve was revealed for all to see. All her hard-won spirituality and self-criticism, suffering, striving for goodness, humility, love and capacity for self-sacrifice flowed from her now in the glow of her radiant eyes, her gentle smile and every feature of her tender face.” (1055)

Energetic and immature Princess Natasha flits about from love to love, from passion to passion, oblivious to the pains of the real world. But when her naiveté is abused, she is left broken and undone. She believes her life is over. However, through caring for the brokenness of another, her “spiritual wound, one that comes from a laceration of the spirit,” begins to heal and push life back into her being. “When love reawakened, life reawakened.” (1202)

Passive and miserable Pierre fails in his search for purpose and finds himself in a state of emotional and physical oppression. Yet, through the loss of his freedom, his wealth, his privilege, his delicacies, and his ideals, he discovers the transformation he so desires. He summarizes, “They say: misfortunes, sufferings. Well, if someone said to me right now, this minute: do you want to remain the way you were before captivity, or live through it all over again? For God’s sake, captivity again and horsemeat! Once we’re thrown off our habitual paths, we think all is lost; but it’s only here that the new and the good begins. As longs as there’s life, there’s happiness. There’s much, much still to come. I’m saying that to you.” (1118)

The stories of Marya, Natasha, and Pierre challenged me to view life not through my momentary discomforts, but through God’s “authorial” view. They also reminded me of the universe’s most privileged Son, who gave up his wealth and comfort for our blood-drenched and war-torn planet, so that through his suffering we might share in his inheritance and peace. He fights our war. He is our peace. Tolstoy is right. Love awakened life. Marya is right. Self-sacrifice produced true beauty. Pierre is right. There’s much, much still to come.

So, read the Bible. No literature could ever take its place. Read great Christian books. We need to hear the voices of our brothers and sisters through the centuries. But also make time for great literature. Read Big Old Books and find your Christian life enriched.

**Page numbers from Penguin Classics 2005 edition, Translation by Anthony Briggs

Editor's Note: Want to read more B.O.B.s, but not sure where to start? Be sure to enter our giveaway here to win A Christian Guide to the Classics by Leland Ryken!

Josh Irby (MDiv, RTS) recently returned to the States after more than a decade with Cru in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina. He is the co-author of Cross on a Hill: A Personal, Historical, and Biblical Search for the True Meaning of a Controversial Symbol.

Related Links

Podcast: "Christians and Lit"

"Beauty Embodied" by Pierce T. Hibbs

"Updating Tolstoy" by Carl Trueman

"The Terrible Speed of Mercy" by Daniel Train

The Messiah Comes To Middle Earth by Philip Ryken

"C.S. Lewis: Apologetics for a Postmodern World" by Andrew Hoffecker [ Audio Disc | MP3 Disc | Download ]