Tertullian's View of the Trinity

The Trinitarian formulations of the early Church often seem to our postmodern culture as the inevitable brainchild of monastic orders, burlap habits, deserts, and Neoplatonic philosophy. Austere, abstract, and unconnected from everyday life—just like the stereotypical image of a monk. Even worse, in a fit of postmodern amnesia, it is no less than the Christian community who has lost sight of the significance of the Trinity for the Christian life. Does it really matter whether we refer to God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit? Are these not simply human conventions imposed upon an infinitely loving being? Have we not outgrown such small-mindedness? What could detailed, protracted arguments over the terms perichoresis, hypostasis, communicatio idiomatum, monarchia, and oikonomia possibly offer the 21st century Church in terms of its devotion to Christ and the growth of His Church? Won't our God-consciousness simply choke and die on the dust of such dogmatic doctrine?

It is precisely this modern God-forgetfulness in reference to the doctrine of the Trinity that belies much of the modern lack of depth, awe, and reverence. First and foremost, the debates about the Trinity were not simply semantic spats among would-be philosophers. These controversies generally arose like Church controversies arise today: In the pew and the pulpit. And thus, the men that answered the challenges were generally pastors and laity committed to the Word of God and salvation by God's grace.

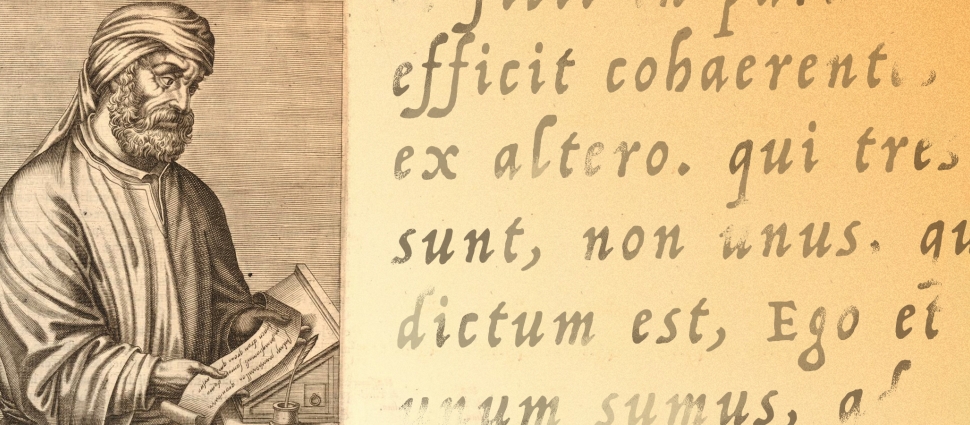

If you read authors like Tertullian (c.155–230 A.D.) and note an undercurrent of impatience, sorrow, and brokenness, it is because these men witnessed the declension of many Christian friends and brethren from the faith. Why would Tertullian—who lived through at least three major Roman persecutions of Christians—defend the Trinity so fervently?

Because he cared about how we should speak and think about God. How do we make sense of the revelation of Scripture that God is Father, Son, and Holy Ghost? How do we grant full weight to all of what is revealed? And how does this impact our salvation? These are the vital questions that Tertullian and others sought to answer.

The doctrine of the Trinity is by no means the easiest doctrine to articulate—and not because most of the theological terminology is developed from patristic Latin and Greek. It is a difficult doctrine to understand because we are touching upon the question of how God exists as God. Our creaturely minds cannot comprehend how God exists as God, but only that God exists as God and, furthermore, only in what manner God reveals himself to us in Scripture. Here a strong and much needed caveat is in order, one with which I think the Church Fathers would heartily agree: We may only assert ultimately what Scripture asserts, and speak guardedly about what we infer from it. We cannot plumb the depths of this doctrine. Thus, the doctrine of the Trinity is the grammar of what we must say and of what we may not say. It consists in boundary markers, as it were.

In light of this, it is worth looking back to a couple figures in the western, Latin branch of the Church who clarified, expounded, and defended the doctrine of the Trinity. And we can begin with Tertullian himself.

In Adversus Praxeas (c. 210 A.D.), Tertullian laments that the true doctrine of the Trinity is more than likely to confuse, much less enlighten the simple, or average, Christian. In Tertullian's day, Christians lived in a polytheistic environment and, consequently, were extraordinarily sensitive to any doctrine that might be construed as a threat to their beloved (and oftentimes newly believed) monotheism. It is no small point to say that Tertullian was defending the traditional doctrine of the Trinity and was not originating it. Throughout Adversus Praxeas, he speaks as a representative of a "we." For example Tertullian says, "we, however, as we indeed always have done ... believe that there is only one God."[1] Or again, pressing Praxeas to prove his points from Scripture like "we" do, Tertullian demands "You ought to prove plainly, however, your points as we ourselves prove that He made His Word a Son to Himself."[2] This "we" refers to the orthodox belief as handed down, as Tertullian says, "from the beginning."[3]

As far as terminology is concerned, Tertullian speaks of a divine economy (oikonomia) within the Trinity. That is, it is proper to speak of the divine rule of God, or monarchy of God (monarcia), as fundamentally unified, and yet diverse in respect to each persons' function in our redemption. Thus, God the Father has a will encompassing all of Creation and Redemption, God the Son accomplished that will, and God the Holy Spirit applies the work of the Son according to the will of the Father to believers. There is a consequent unity of purpose, yet diversity in its operation. On this point, for example, Tertullian exposits John 10:34-38,[4] where Christ says that He is in the Father, and the Father is in Him,

"...it must therefore be by the works that the Father is in the Son, and the Son in the Father; and so it is by the works that we understand that the Father is one with the Son."[5]

This point offers a great amount of clarity by preventing the confusion of the Father as the Son (and vice versa). It also maintains the distinctiveness of their persons and the unity of their essence, or substance (substantia). Tertullian reiterates the distinctiveness of the Holy Spirit saying, "Thus the connection of the Father in the Son and of the Son in the Paraclete makes three coherent ones [TR - persons], one distinct from the other; these three exist as one essence, not as one person, just as it is said 'I and my Father, we are one," in respect to the unity of substance, not to the singularity of number.[6]

We should now compare Tertullian's formulations[7] with the Nicene Creed:

Tertullian, Adversus Praxeas

... believe that there is one only God, but under the following dispensation... that this one only God has also a Son, His Word, who proceeded from Himself, by whom all things were made, and without whom nothing was made.

Him we believe to have been sent by the Father into the Virgin, and to have been born of her-being both Man and God, the Son of Man and the Son of God, and to have been called by the name of Jesus Christ;

We believe Him to have suffered, died, and been buried, according to the Scriptures, and, after He had been raised again by the Father and taken back to heaven, to be sitting at the right hand of the Father, and that He will come to judge the quick and the dead; who sent also from heaven from the Father, according to His own promise, the Holy Ghost, the Paraclete, the sanctifier of the faith of those who believe in the Father, and in the Son, and in the Holy Ghost.

The Apostle's Creed

I believe in God, the Father Almighty, the Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, His only Son, our Lord:

Who was conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended into hell. The third day He arose again from the dead. He ascended into heaven and sits at the right hand of God the Father Almighty, whence He shall come to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting.

With Tertullian we have an early voice attributing his basic understanding of the Trinity to a Scripturally-based tradition handed down in the Church. Furthermore, he engages polemically with Praxeas on the basis of Scripture, expounding a plethora of verses from the Gospel of John. Remember that the Marcionites, modalists, and others claimed support from the Gospel of John specifically because it did not have an "earthly" genealogy of Christ. Thus, Tertullian succeeded in beating them at their own game, even pressing them to utilize all of Scripture in the Old and New Testaments.

Lord permitting, next time we will consider another Latin author who, like Tertullian, did much to explain and defend the doctrine of the Trinity.

Todd Rester (PhD, Calvin Theological Seminary) is associate professor of church history at Westminster Theological Seminary in Glenside, PA.

Related Links

Mortification of Spin: "The Trinity Debate"

"Proverbs 8:23, the Eternal Generation of the Son and the History of Reformed Exegesis" by Nick Batzig

"The First Baptist Theologian: Tertullian" by Aaron Denlinger

Knowing the Trinity by Ryan McGraw [ Paperback | eBook ]

The Essential Trinity, ed. by Brandon Crowe and Carl Trueman

The Holy Trinity (Revised and Expanded) by Robert Letham

Notes

[1] Tertulliani Adversus Praxeas Liber, 2. "Nos vero et semper, et nunc magis ... unicum Deum credimus."

[2] Tertulliani Adversus Praxeas Liber, 11.1 "Probare autem tam aperte debebis ex scripturis, quam nos probamus illum sibi filium fecisse sermonem suum."

[3] This idea that Tertullian was preserving an orthodox tradition is not original with me, see Benjamin B. Warfield's extraordinarily helpful articles "Tertullian and the beginnings of the doctrine of the Trinity" in The Works of Benjamin B. Warfield, Vol 4, p 1 - 109.

[4] (ESV) John 10:37-38 "If I am not doing the works of my Father, then do not believe me; but if I do them, even though you do not believe me, believe the works, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me and I am in the Father."

[5] Tertulliani Adversus Praxeas Liber, 22.13 "per opera ergo erit pater in filio et filius in patre, et ita per opera intellegimus unum esse patrem <et filium>"

[6] Tertulliani Adversus Praxeas Liber, 25.1 "ita connexus patris in filio et filii in paracleto tres efficit cohaerentes alterum ex altero. qui tres unum sunt, non unus, quomodo dictum est, Ego et pater unum sumus, ad substantiae unitatem non ad numeri singularitatem."

[7] Tertulliani Adversus Praxeas Liber, 2.1-4

Editor's Note: This post was originally published on reformation21 in Novemeber of 2006.